My daughter recently declared that I am a “premium adult.” I’m not entirely sure what that means, but I like the sound of it. Apparently, I have skills and knowledge above the beginner level, though I don’t check all the boxes.

For instance, I don’t have matching towel sets or feel smug about my multiple drawer and cabinet organizers. But I do use cloth napkins, have retirement accounts, keep folders for current and past taxes, and hold strong opinions on the proper way to fold a fitted sheet. Bonus points: I’ve figured out you can make a bed using only flat sheets—it’s easier, and they fit every time. Folding problem solved.

Premium adults know things newbie adults don’t. My kids were shocked to discover their dishwashers have filters. They were even more shocked (and maybe a little grossed out) to learn those filters need cleaning. They weren’t surprised that I knew this and do it. They haven’t.

Their questions cover the full spectrum of “How do I adult?”—from choosing a doctor from a vast HMO list to eliminating the lingering cat pee smell left by a roommate. My solutions aren’t always popular. One child had to replace carpet. The other still hasn’t made the doctor’s appointment.

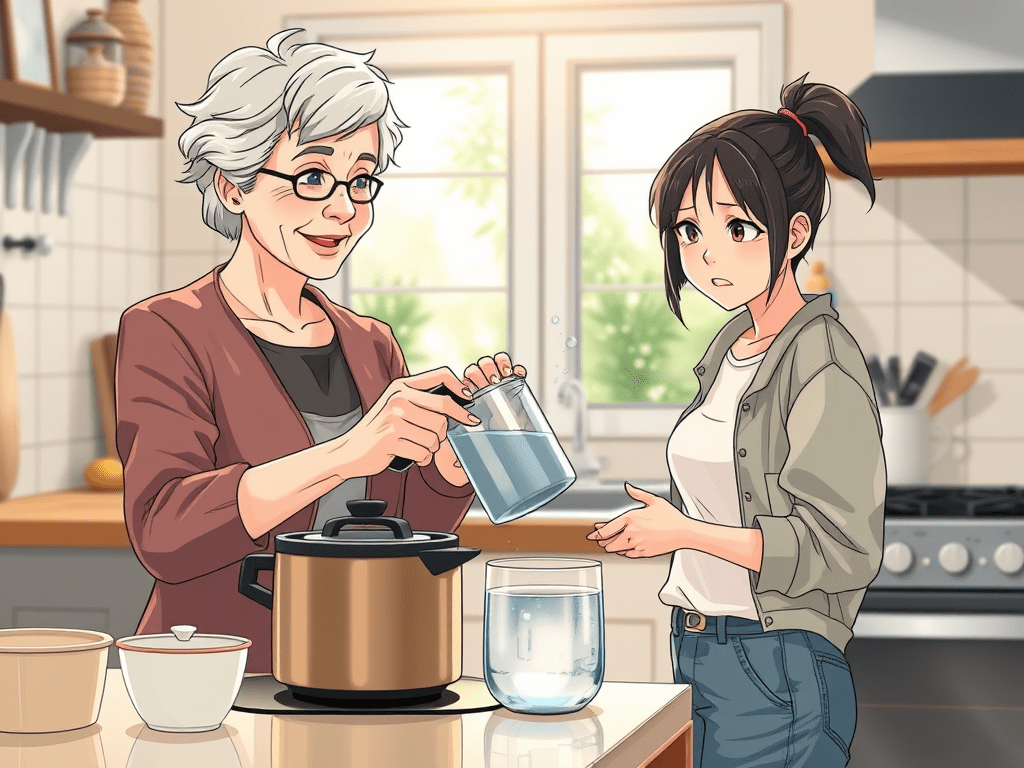

Some issues are laughable to fellow premium adults. Take boiling water. It sounds foolproof, but it requires surprising amounts of skill, knowledge, and courage. Step one: overcome fear of open flame. Step two: know what size pot to use, how much water to add, how high the flame should be, and what “boiling” actually looks like.

Sure, you could Google it, but apparently, a lot of people still don’t know. One YouTube tutorial on boiling water has 1.9 million views. Pasta-cooking videos abound, each with its own rules. Mine: add a tablespoon of salt, never oil, and stir to prevent sticking. But why would you when your mother is a premium adult.

My son calls for cooking help, too—mainly to decipher the sloppy cursive and minimal directions in my family recipe book. My chili recipe lists ingredients but offers only: Brown the meat. Add everything else. Simmer until flavors blend. I’ve also coached him through replacing a water heater, repairing siding, and banishing the infamous cat pee smell.

I’m not bullet proof, though. Recently, my son had to bow out of a family fun night. We seldom have all four of us in the same location now that the kids have flown the nest. Happily, everyone’s schedule came together so we could celebrate our daughter’s birthday. She requested hot dogs grilled by her brother. He was all on board, then he wasn’t. The night before the celebration, he texted to say he felt sick. By morning, he had fever, aches, congestion—the works.

While in Meijer with my daughter, I took his call. He listed his symptoms and mentioned his temperature. A few seconds later, my brain caught up, and I texted back my “premium” alarm:

“That’s a high fever. Take Tylenol or ibuprofen. Call me in 30 minutes. If it’s not down, I’m taking you to the hospital.”

Thirty minutes later, he replied:

“Mom, I think you misheard me. It’s 100.4°, not 104°.”

Side note: My children insist I need hearing aids. I insist they mumble. The ear doctor sided with me—they mumble.

To my credit, 104° is an emergency. 100.4° barely registers. It’s a “why are you even calling me?” temperature. But I know why he was calling.

When you’re sick, you miss your mom—premium or not.